The importance of the automotive sector for Europe’s emerging markets can hardly be overstated. The automotive sector is the largest contributor to GDP in Hungary, Akos Eros, Partner at Squire Patton Boggs (SPB) in Budapest, points out, and Uros Ilic, the Managing Partner of the ODI Law Firm, describes a similar prominence in Slovenia: “The automotive sector represents as much as 20% of Slovenian exports, making it a particularly important component of the country’s economy.”

Across the region, “every country is doing all it can to draw in these production plants, a competition in which every country is trying to put forward better infrastructure and supporting through different facilities,” according to Martin Wodraschke, Partner and Head of CEE German Desk and CEE Automotive team at CMS.

We reached out to leading lawyers in this sector across Central and Eastern Europe to learn more about the amount and kinds of work being generated and the particular challenges the sector imposes on those lawyers working within it.

A Look at the Market

Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland are among the CEE countries most commonly identified as heavy manufacturers.

“…every country is doing all it can to draw in these production plants, a competition in which every country is trying to put forward better infrastructure and supporting through different facilities…”

In Hungary, CMS’s Wodraschke reports that the manufacturing side of the industry is still growing, encouraged by large suppliers such as Bosch and Continental. According to Lukasz Berak, Partner at Soltysinski Kawecki & Szlezak (SK&S), although Poland claims fewer production facilities for passenger cars than Slovakia, sales and distribution remain strong.

While “there is no real automotive production industry in [Slovenia],” according to Matija Testen, Partner at Rojs, Peljhan, Prelesnik & Partners (RPPP), “there are some strong producers on the supplier side, such as Johnson Controls and CIMOS.” Ilic at ODI Law explains that, in Slovenia, “there are over 16,000 people employed in automotive in the country between some 250 companies that create a regular stream of legal work on daily commercial, labor, and regulatory matters. This cluster ranges in products from decorative components to engines and engine parts, to gearing equipment, to electronic components. Many leading automotive players have Slovenian firms as partners: Audi, BMW, Daimler, VW, as well as MAN and Ford in Germany account for some 40% of car component exports from Slovenia followed by buyers in France, Italy, Austria, the UK, and the USA. The vehicles that roll off the assembly lines of Renault, PS, Skoda, and Fiat also incorporate components from Slovenia that comply with all EU green and safety requirements. In figures, it means that Slovenia’s automotive industry generates roughly one tenth of the country’s GPD and accounts for 14% of its exports of goods.”

Daniel Anghel, Partner at PwC in Romania, explains that Romania hosts “a lot of spare parts suppliers, most of them held by foreign groups but some locally-owned as well, located especially in the west of the country but increasingly towards the center as well.” And in Macedonia Gjorgji Georgievski, Partner and Regional Head of TMT Group at the ODI Law Firm, refers to the recent establishment of a large Johnson Controls plant in Macedonia (see Buzz on page 28).

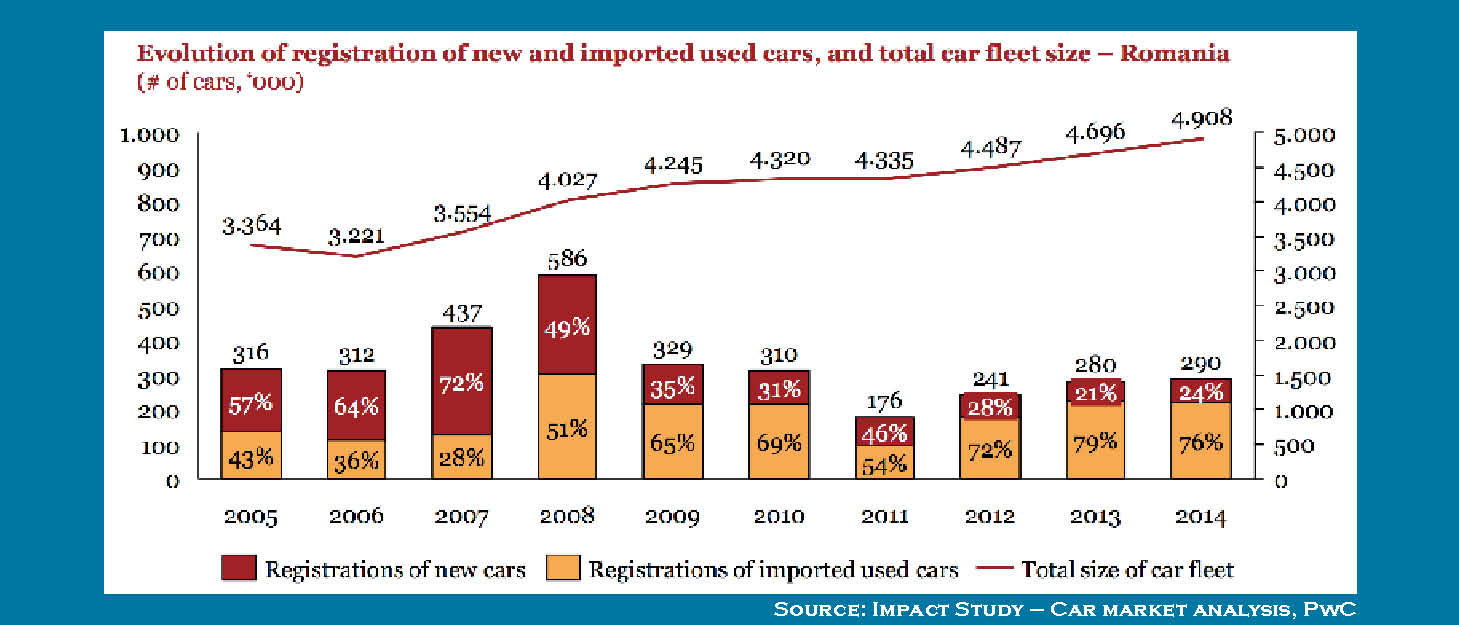

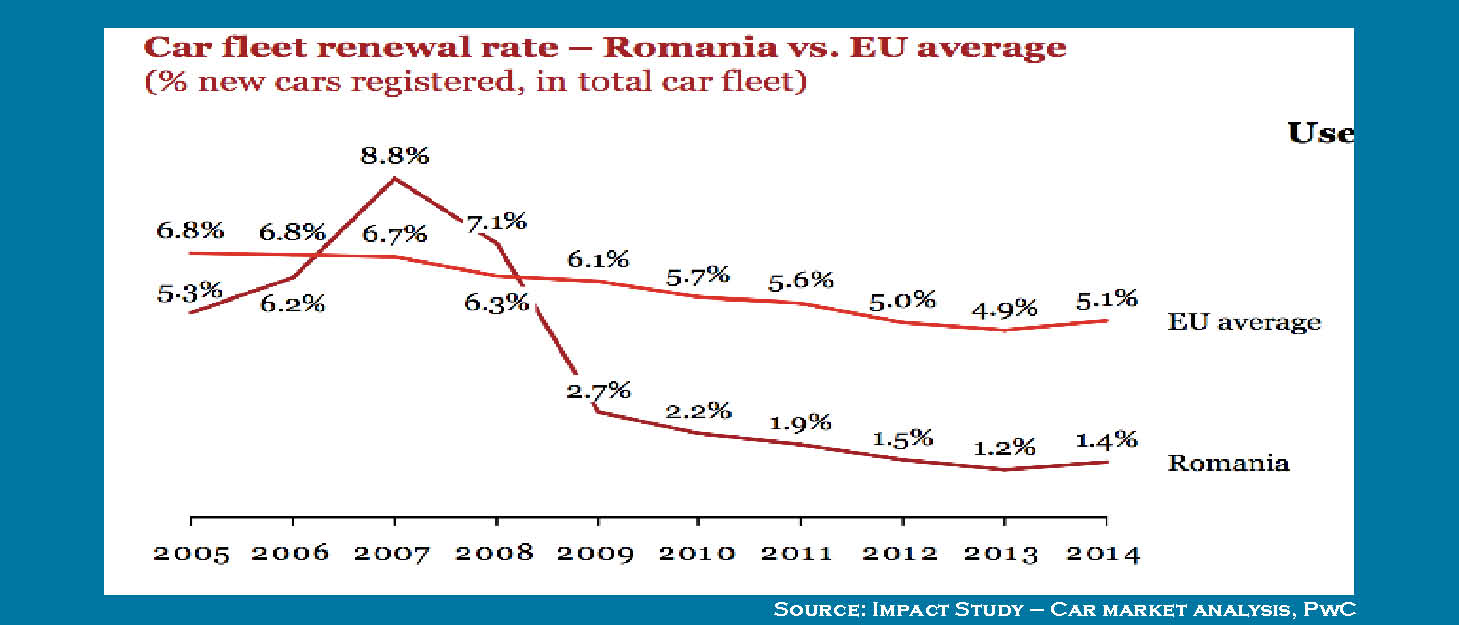

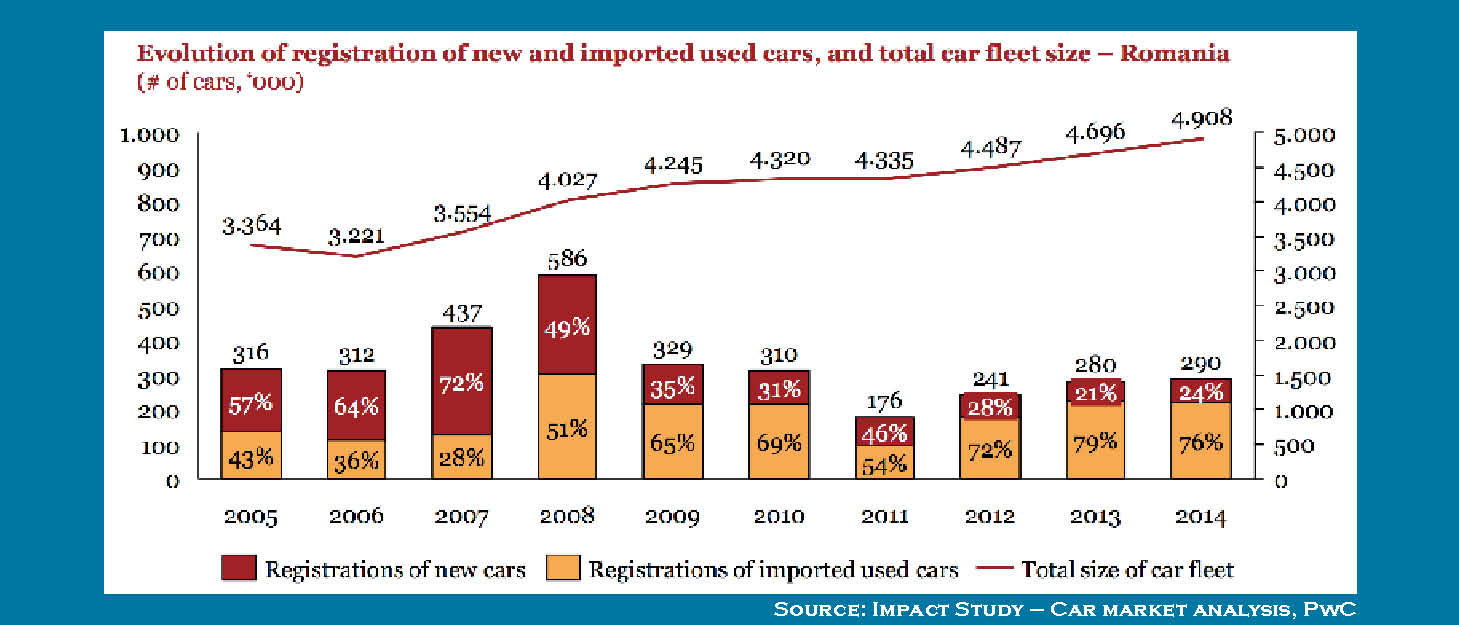

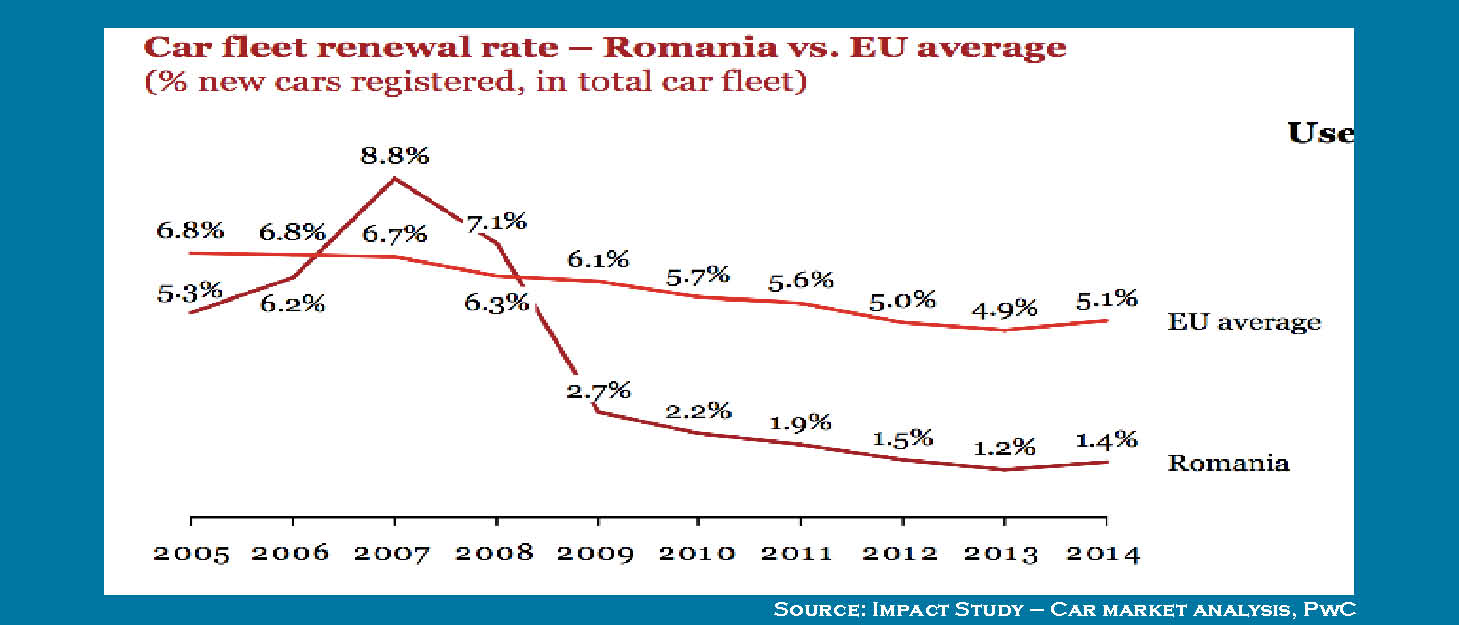

Most CEE countries reported steady automotive sales in 2015, with SK&S’s Berak pointing to Poland’s constant sales growth as an exception, “which makes both networks and manufacturers quite happy.” Of course, buying a new car is not the only option on the table for consumers, and manufacturing of new cars is impacted by an apparent increase in used car sales, mentioned as a factor both by Berak in Poland and Anghel in Romania. Anghel reports that, “starting with 2007/2008 especially, Romania developed into a second-hand market, unfortunately,” and points to a recent PwC study showing that second-hand cars were outselling new cars 4-1 in the country (see Graphs for more details).

Keeping Lawyers Busy

With all this activity, there is plenty of work for lawyers specializing in the automotive sector across the region. CMS’s Wodraschke explains: “The huge original equipment manufacturers present in the country generate work for lawyers in pretty much all areas, with a lot of work coming from commercial and employment areas in particular, complemented with some M&A activity as well, since some clients are also looking at smaller targets they’d like to acquire.”

In Russia, Daria Shagabutdinova, Head of the Legal and Corporate Affairs Department of Cordiant, has noticed quite a bit of M&A activity as well, with “boards aiming to incorporate start-ups when possible or selling off less-performing assets.” Veronika Odrobinova, Partner at Dvorak Hager & Partners (DH&P), also reports a lot of M&A activity in the Czech Republic, and she says that she has noticed a “push from the larger producers who are seeking to get more efficient and relocate their businesses or are getting rid of different parts that are not efficient.” She adds that this is complemented by investors coming from outside the country and consolidation in the sector within the country, with a number of new plants also being developed.

While these types of projects tend to be one-offs, there appears to be a significant amount of recurring work as well, with real estate and employment matters being most common, according to Odrobinova, though she reports that the considerable amount of financing work that existed two or three years ago seems to have dried up.

Eros at SPB identifies labor law matters as a common form of ongoing work after the initial set-up stage is completed – inevitable, he says, in a “sector that is very employee-intensive.” His team makes “some additional regular check-ins … on the contracts in place to make sure that the templates are still compliant in case a regulator update happens, but nothing as intensive as the original set-up stage.”

Of course, the very nature of the sector limits the amount of ongoing assistance clients require after set-up. Eros notes that although the set-up stage is work-intensive for lawyers, once manufacturing facilities are up and running there’s less to do. “The beginning … involves a lot of work to set up the greenfield investments, secure the real estate purchases, assist in the subsidies negotiations, set up the employee base, set up financing, and so on.” Even real estate matters are challenging, as “it’s not a simple matter of purchasing a plot of land. It involves considerable negotiations with municipalities, infrastructure work, and so on.” By contrast, “after the plant is set up there are not so many legal projects, at least hopefully.”

Indeed, contract work is fairly limited in the region, according to Prague-based DH&P Partner Odrobinova, “since, most of the time, cars are produced for a mother company abroad.” CMS’s Wodraschke elaborates: “on paper, these companies don’t really sell anything to end users, meaning that consumer rights are not really within the scope of concerns of the local manufacturing plants. Even in terms of suppliers, Audi Hungary for example does not really purchase spare parts from Delfi Hungary, Look Hungary, or Hilite Hungary – rather, a global or European deal is in place. There are exceptions, of course, [and] one of our clients, for example, has its European HQ in Hungary, but such instances are very rare.”

Of course, some lawyers in the automotive sector – particularly, perhaps, those working in-house – deal more with contractual matters than others. For example, Nikolay Khaybulaev, Director for Legal Affairs and Government Relations at Mazda Motor Russia, explained that his team’s activities revolve primarily around contract law, “as part of your team’s role in supporting the business side is retaining contractual relationships primarily.” According to Khaybulaev, this is complemented by regulatory work and “some work on trademark-related issues and some litigation” (though he notes that his company “really tries to solve most issues in an amicable way”).

On the Horizon

Several lawyers in the automotive sector in CEE note the affect of significant anti-monopoly developments in their jurisdictions. In Russia, Khaybulaev says, a new Code of Conduct for Members of Automobile Manufacturers, developed in cooperation with the country’s Federal Antimonopoly Service, has been put in place to ensure that the industry follows certain rules regarding dealerships. Dealers who believe those rules are being violated, Khaybulaev explains, “can apply to the anti-monopoly service, a development which has seen many companies in the sector invest a lot of effort to review existing systems/contracts and make sure they are compliant to the full letter of the law.”

In Slovenia, Testen at RPPP refers to a recent decision against the Hyundai group – a general importer – related to warranty clauses linked to authorized repair shops deemed to be in breach of competition regulations. SK&S’s Berak described antimonopoly issues connected with dealership networks as “a recurring theme” – particularly related to pricing, with producers only allowed to recommend rather than specify the prices offered by the dealer. According to Berak, this is a matter that is “stringently controlled by the Polish anti-monopoly watchdog.”

At the same time, both Poland and Romania are taking active steps to address an aging car fleet. In Poland, Berak points to a new consumer protection law that entered into force at the end of 2014, as well as legislation addressing end-of-life vehicles, increasing various requirements on distributors and dealers as creating new work for lawyers in that country. For its part, Romania is pursuing initiatives related to environmental stamps and other pieces of legislation meant to address the aging car pool in the country, according to PwC’s Anghel – “initiatives that despite being changed around several times proved to have a positive impact in the past.”

the decision by many manufacturers to locate their plants in the region is driven by “some opportunities generally valid for CEE as a whole – cheap labor costs and good infrastructure and access within CEE.”

Relevant labor law is being updated as well, according to CMS’s Wodraschke, who says that the 2012 labor code in Hungary has already been changed several times in the last few years to “give more flexibility and implement many [changes] relevant to the industry, which overall made the life of companies much easier in the country.” Less positive news on the subject comes from Romania, where Anghel points to “recent heated talks” related to a raise of the minimum wage in the country, which would, “of course, make the manufacturing industry in the country less competitive on the cost side.” A more positive development, he says, is the initiative to remove the so-called “pole tax” – a tax on special equipment that was hurting the industry: “We ran a study and noticed that companies would have to repay up to 60% of the value of special constructions, which represented a block [against] purchasing new technologies. We expect the development will have a positive effect towards this end as the pole tax would be eliminated next year.”

An update in Russia last year required that companies holding individuals’ personal data collect, store, modify, and host this data within Russia. Khaybulaev describes this, however, as more of a financial and infrastructure burden than one requiring significant legal advice. The ongoing Western sanctions on Russia, Khaybulaev explains, have a relatively insignificant impact on his legal team (as distinct from their effect on the country as a whole, of course), and he claims they have had only a minor impact on the company itself.

Finally, SK&S’s Berak reports that while consumer protection legislation in Poland in the main mirrors European standards and requirements, the overlap between the product warranties extended by car makers when selling to customers and the Polish statutory warranty (governed by civil law provisions) creates a problematic “dual system of protection.” According to Berek, “in practical terms, [this] means that Polish consumers are able to choose between the two, which poses some complications when in need of solving disputes with consumers.”

Chasing the Plants

CEE does have an advantage in enticing many automotive manufacturers. As SPB’s Eros explains, the decision by many manufacturers to locate their plants in the region is driven by “some opportunities generally valid for CEE as a whole – cheap labor costs and good infrastructure and access within CEE.”

This is not to say that all CEE markets are identical. Speaking about Romania, Anghel comments, “The potential is great. I see a lot of room for growth, both in terms of suppliers of components but also in the producers’ space especially, [although] that seems to be impeded by people’s concern over underdeveloped infrastructure.” He points to Daimler Chrysler which, considered the

Romanian market, then – because of this concern – decided ultimately to invest in Hungary and simply hire from Romania. Anghel notes, however, that “we are seeing a few good things in the area of infrastructure but, unfortunately, progress on this front is slow.”

And it is not just infrastructure that affects this competition. According to ODI’s Uros Ilic, “Slovenia cannot really compete on the lower value-added production side in terms of cost of labor, with the country being very well positioned comparatively when it comes to skilled or highly-skilled workforce.” Not everyone is so lucky. CMS’s Wodraschke says that, “it is difficult to get good skilled workforce in the big industrial zones of Hungary and in the region as a whole. In the north of the country, there are some production plants that are trying to get employees from Slovakia, but even there they have the same challenge.”

Efforts are being made to meet this demand, and Wodraschke reports that many supplies manufacturers are setting up strategic collaborations with technical schools in Hungary. Establishing such projects can provide interesting work for lawyers, both on the level of obtaining available European aid and in structuring the actual agreements between the companies and the educational institutions. Similar efforts are reported in Romania by Anghel, who says that there is a drive towards switching from a simple assembly and low value-added production to a more complex approach. He gives as an example the so-called “Centrul Tehnic de la Titu” from Dacia, which hosts 2,000 engineers focused on R&D, as a positive sign towards this goal. Anghel sees progress being made, “not only in the automotive sector, but [in] manufacturing in general, with such co-operations between manufacturers and technical universities being set up in the cities of Timisoara, Cluj, and Oradea.”

Attracting Investors and Manufacturers

Ultimately, the incentives to develop the necessary infrastructure, provide enticing tax breaks, and create workforce development programs all make sense, as Wodraschke’s observation about Hungary seems to apply to most of the CEE markets as well: “Hungary is a manufacturing place. Therefore, it is not surprising that state bodies are in regular contact with the large manufacturers and have a very proactive economic policy towards them and are eager to establish favorable circumstances for investors and manufacturers.”

We thank the following for sharing their opinions and analysis for this report:

- Daniel Anghel, Partner, PwC

- Martin Wodraschke, Partner, CMS,

- Matija Testen, Partner, RPPR

- Veronika Odrobinova, Partner, Dvorak Hager & Partners

- Lukasz Berak, Partner, Soltysinski Kawecki & Szlezak

- Uros Ilic, Managing Partner, ODI Law Firm

- Akos Eros, Partner, Squire Patton Boggs

This article was originally published in Issue 3.1 of the CEE Legal Matters Magazine. If you would like to receive a hard copy of the magazine, you can subscribe here.

“People have gotten used to the new normal,” Kuleshov said, “and we’re seeing a good deal of work coming from divestment of non-core assets as well as some potential acquisitions on the horizon as well.” Another potential source of business that he mentioned was privatizations, with the Russian government planning to sell a number of state-owned companies to private investors. “With Mr. Putin mentioning that the priority would be to sell to Russian private clients, I can only hope that will include some of our clients.”

“People have gotten used to the new normal,” Kuleshov said, “and we’re seeing a good deal of work coming from divestment of non-core assets as well as some potential acquisitions on the horizon as well.” Another potential source of business that he mentioned was privatizations, with the Russian government planning to sell a number of state-owned companies to private investors. “With Mr. Putin mentioning that the priority would be to sell to Russian private clients, I can only hope that will include some of our clients.”