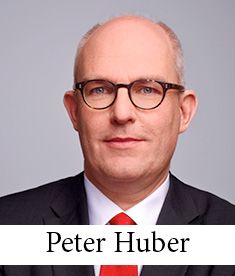

The CEE region is registering a growing interest from renowned private equity firms and an increase in large transactions involving reputable market participants. We sat down with Peter Huber, the Managing Partner and Head of the International Transactions Team at CMS in Austria. His team was recently involved in the Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co (KKR) acquisition of the SBB/Telemach Group, one of the leading Internet and cable operators in south-eastern Europe (i.e., Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and Macedonia) with more than 100 million customers. Coordinated by CMS Vienna and Belgrade, this transaction was the first investment of KKR in the region.

CEELM:

In your view, what are the main drivers for the increased interest in the CEE region from PE firms?

P.H.: I believe there are a multitude of factors at play. Certainly, a lack of attractive investments in more established PE markets is a big driving force towards this region. At the same time, pricing in the region remains relatively attractive. The bottom line is that PE firms are always looking for markets that hold the promise of attractive returns, and I believe CEE holds this promise.

Another aspect is that these markets are now offering an increase in the supply of secondary situations, where PE firms that invested in the region 5-6 years ago and who are not reaching the end of their investment cycle are now looking to sell.

Lastly, I would say that there is also a changing attitude towards risk that can be observed among the major PE players. Having major US and UK equity houses turn towards CEE will have a strong impact on making these markets more established on the PE global landscape. In light of this, the Telemach deal is in many ways an icebreaker for the region.

CEELM:

Since you mentioned risk, do you believe the risk profile of CEE markets has decreased recently or that PE houses turning towards the region are simply less susceptible to it?

P.H.: I’d say that to some extent, both apply. On the one hand, it is surely the case that the perceived risk levels have generally decreased, especially for investments in the EU member state regions – but also in those markets bidding for accession. At the same time, I also believe that these firms have put in place more effective processes to identify, price, and manage existing risk, including very rigorous due diligence exercises.

CEELM:

What are the main jurisdictions in terms of attractiveness, and which ones are lagging behind?

P.H.: Poland and the Czech Republic are perceived as the most stable markets for various reasons: their finances, the size of their respective markets, EU membership, etc. When we look further afield, Slovakia, although a smaller market, is potentially attractive; however it does raise the question as to whether there are enough potential targets in the country simply due to its size. Romania is another market that is relatively attractive.

Serbia and some other Balkan countries also have significant potential at this point in time. Serbia still possesses the legacy of a former industrial hub for the region. It also has quite a few “secondaries” taking place, but it needs to manage the perception towards them, especially in terms of financing. I believe – and this view is shared by other market observers – that the KKR investment in SBB/Telemach, which apart from Serbia involved several other markets in the SEE region, will in many respects act as an icebreaker transaction.

CEELM:

What are the main industries you believe will attract most investment in the short or mid-term period and why?

P.H.: Telecom and media will definitely continue to grow since there are quite a few promising companies in these industries. PE will likely pick-up companies in these areas and strategic investors here will likely represent a spearhead for PE companies in the region, depending, of course, on the flexibility of regulators in allowing them to branch out.

Other high potentials can be found in the food and drinks industry, and it is likely we’ll see some movement in the retail space as well, all of which are relatively lagging behind but are, for the most part, undergoing consolidation in many markets in the region. PE firms could act as a catalyst in this process.

CEELM:

In light of current events, has the deal flow towards Russia and Ukraine decreased? If so, where is it being redirected?

P.H.: To some extent, these markets have always had a high profile of risk, meaning they have always been viewed as problematic from a PE perspective. Interestingly, if you look at most statistics, the Russian market has led – and still is leading – the charts in terms of PE investments. But that does not always present the most accurate image, since the boundaries between PE investments and private investments as well as investments by corporations controlled by high net worth individuals are rather blurry.

What I can say is that, based on what I am hearing from my colleagues in Russia, international PE investors are sitting on the sidelines at the moment and waiting to see how things unfold. We have seen some exits from these markets from both international and regional PE houses but I have a hard time imagining that the ones who are still on the ground will pull out in the mid-term. Naturally, in terms of new investments, there is a significant slowdown.

CEELM:

From a regulatory standpoint, what do you believe are the biggest challenges for PE Funds looking at CEE Markets? What are the main recurring risk factors that these firms take into account when looking at the region?

P.H.: You do need to differentiate between EU members, including those markets negotiating their accession, and other markets. For the most part, the typical emerging market’s risk factors come into play: foreign exchange risk, repatriation of profits concerns, risks of nationalization or quasi-nationalizations, risks of asset freezes, the general risk of enforceability of legal contracts, and general corporate governance, compliance, tax, and merger control risks. What I notice is that players who become committed to the region have developed very effective tools to assess, manage, and price these risks.

One of the biggest factual barriers is therefore the investment required for a PE house to familiarize itself and become comfortable with the peculiarities of the markets in the region. But for a second investment, things are much easier. What I would expect is that the houses which have recently made a significant investment in the region will likely continue to remain active in these markets in the future.

CEELM:

We spoke a lot about potential investors from the US or UK. What about other potential ones?

P.H.: We might see more investments from Asia, i.e. from markets such as China, and maybe Singapore – if we include direct investments of sovereign wealth funds in our definition of PE – but I can’t really point for sure towards systematic efforts in the CEE/SEE region to attract such investments.

CEELM:

With more firms turning towards the region, is CMS likely to expand its Private Equity team to match its offering to the increased demand? If so, in what jurisdictions will that likely happen?

P.H.: Naturally, we always try to react to market changes and increased demand. One recent example of this is the fact that we now have a team in place in Turkey that is well equipped to advise on PE transactions. They are our youngest office in the region but have already been quite active in the PE field. We have also dedicated resources to increasing our team in the Balkans and will likely continue along these lines as the market develops.

CEELM:

While the two are not mutually exclusive, as a general strategy, is CMS trying to build a client base consisting of PE funds interested in the region or local companies looking to sell? Why?

P.H.: In both the recent and not so recent past, we have more often advised PE houses, co-investing supra-nationals, or corporates buying from PE. Occasionally we have also advised local companies or to a lesser extent the management of local companies. Overall, we do tend to focus strategically on advising PE houses or international corporates buying from PE as we feel that this type of work allows us to apply our expertise in the best way possible.

This Article was originally published in Issue 5 of the CEE Legal Matters Magazine. If you would like to receive a hard copy of the magazine, you can subscribe here.

Erik Steger, one of three Managing Partners at Wolf Theiss in Vienna, explains that in the first years of the transition to a post-communist economy in the former Eastern Bloc countries, “expats could assist in bringing the service level up [and] contribute experience with laws that these countries adopted.” And, once they came in, he suggests, “many more than a handful stayed and will now stay for good, [having] learned the local laws … and often learned the language [so that], today, they are excellent advisors in local law as well.”

Erik Steger, one of three Managing Partners at Wolf Theiss in Vienna, explains that in the first years of the transition to a post-communist economy in the former Eastern Bloc countries, “expats could assist in bringing the service level up [and] contribute experience with laws that these countries adopted.” And, once they came in, he suggests, “many more than a handful stayed and will now stay for good, [having] learned the local laws … and often learned the language [so that], today, they are excellent advisors in local law as well.”

But Clark also believes that Austria’s extremely high income and corporate tax rates (see Graph 1) provide incentive to both firms and lawyers alike to offer their services to Austrian clients from outside the country. According to Clark: “Firms are able to provide more cost-efficient and competitive service to clients by basing their expats in neighboring countries, where costs generally are much lower than in Austria.”

But Clark also believes that Austria’s extremely high income and corporate tax rates (see Graph 1) provide incentive to both firms and lawyers alike to offer their services to Austrian clients from outside the country. According to Clark: “Firms are able to provide more cost-efficient and competitive service to clients by basing their expats in neighboring countries, where costs generally are much lower than in Austria.”

Some people believe that more lawyers would bring the standards down. But I think it would increase the competition and raise the standards. Being a good attorney is about trying and delivering, and being very careful but also very diligent. Hopefully, more competition will be an incentive. On the other hand, I don’t believe that artificially prolonging the trainee period will have a significant impact on young lawyer development. – Veronika Pazmanyanova, Associate at White & Case

Some people believe that more lawyers would bring the standards down. But I think it would increase the competition and raise the standards. Being a good attorney is about trying and delivering, and being very careful but also very diligent. Hopefully, more competition will be an incentive. On the other hand, I don’t believe that artificially prolonging the trainee period will have a significant impact on young lawyer development. – Veronika Pazmanyanova, Associate at White & Case