Greek banks have successfully attracted substantial private investment and diluted public ownership, only a few months after their recapitalization and ensuing de facto nationalization.

Although historically conservative and well-capitalized, the aftermath of the Lehman crisis and the ensuing Greek sovereign debt crisis took its toll on Greek banks:

- depositors feared Greece’s exit from the Eurozone (Grexit) and the possibility of bank insolvency and about one third of deposits were withdrawn from Greece, thereby draining the Greek banking system’s liquidity;

- non-performing loans (NPLs) and related provisioning needs spiked;

- deterioration of Greece’s sovereign creditworthiness led to a deterioration of its banks’ creditworthiness and capital markets borrowing closed;

- the Balkans and other countries where Greek banks had operations (such as Egypt, Ukraine, Albania etc.) experienced similar recessionary trends or political turmoil and the need for the financial support and liquidity of such operations increased; and

- deleveraging (i.e. accelerating loans and ceasing the provision of new ones) was available only to a limited extent.

Consequently, liquidity was severely affected and Greek banks became wholly dependent on European Central Bank funding. Unprecedented losses incurred from the restructuring of Greek sovereign debt and the increase in NPLs adversely affected capital ratios. To sum up, Greek banks were a threat to systemic stability and in dire need of recapitalization, and radical measures were therefore implemented.

The Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) was created in order to supervise the recapitalization and consolidation of the banking sector and manage the holding of banking shares. HFSF was funded with EUR 50 billion.

The Bank of Greece (BoG) did not allow the default of any Greek bank on its deposit obligations and enforced an aggressive consolidation agenda whereby weak banks were dissolved and their assets eventually sold to other stronger banks. International banks that decided to exit the Greek market recapitalized and subsequently sold their Greek banking operations (typically for negative consideration). To-date, only four large banks and two smaller banks have survived.

To address investors’ mistrust on NPL formation and provisioning, BoG engaged Blackrock Solutions to conduct an independent review. Blackrock concluded its work in December 2012 and predicted NPL total losses of approximately EUR 31 billion for the next 3 years.

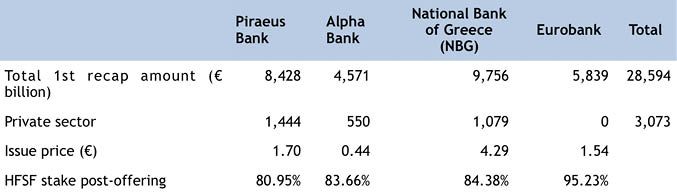

The first recapitalization took place between April and July 2013, after the Greek government’s debt restructuring and the conclusion of Blackrock’s review. HFSF contributed EUR 25.5 billion, while the private sector contributed EUR 3.1 billion:

Under the recapitalization law, if: (i) the private sector contributed at least 10% of the total recapitalization amount required; and (ii) the bank complied with its restructuring plan, HFSF would not be entitled to elect a bank’s board of directors and its management and would only exercise veto rights. Accordingly, Piraeus, Alpha, and NBG’s incumbent private management was retained and only Eurobank’s management was replaced (given the absence of private sector contributions).

As an additional incentive, all private investors that participated in the recapitalization of the aforementioned three banks were allocated free warrants, a listed security granting a call option with a 4.5 year duration on HFSF’s shares at the original issue price (plus interest).

After the completion of the first recapitalization, market conditions started to improve, international markets became optimistic, political instability and the Grexit talk subsided and investors began returning to Greece. BoG commissioned a second review by Blackrock, which was released in early March 2014 and depicted a more positive outlook than expected in the market at the time.

The banks quickly seized the opportunity that arose to: (i) raise additional capital; (ii) strengthen capital ratios, particularly given the application of Basel III reforms; (iii) address capital deficiencies under the second Blackrock review; and (iv) with respect to Alpha and Piraeus, partially repay state aid received in 2009.

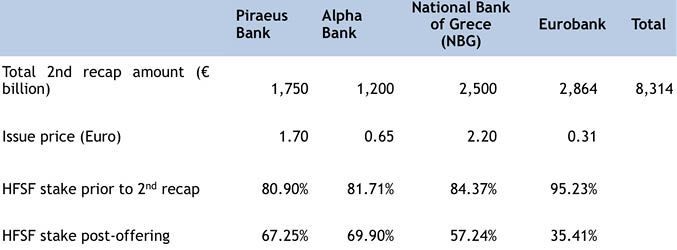

The second recapitalization took place between April and May 2014, raising EUR 8.3 billion from the private sector and resulting in the HFSF’s dilution.

The second recapitalization dramatically changed the Greek banking arena. Eurobank, the weakest bank most severely affected, currently has the highest number of private shareholders that include a group of prime international investors that intend to supervise management. Piraeus and Alpha are clearly the two largest players in the market whereas NBG now has ample time to prepare for the sale of its significant Turkish subsidiary, Finansbank.

The Greek crisis has endured drama and it is impossible to predict its end. However, the above developments constitute a remarkable achievement: the transfer of the Banks from private ownership to public and back again in less than … 14 months! Despite the financial turmoil, the Greek banks succeeded in attracting private investment and are now on their way to recovery.

By Cleomenis Yannikas, Partner, Dryllerakis & Associates

This Article was originally published in Issue 3 of the CEE Legal Matters Magazine. If you would like to receive a hard copy of the magazine, you can subscribe here.

If you would like to receive regular updates on CEE cases, deals, lateral moves and promotions, and legal awards or if you want to sign up to receive a hard copy of our upcoming magazine please

If you would like to receive regular updates on CEE cases, deals, lateral moves and promotions, and legal awards or if you want to sign up to receive a hard copy of our upcoming magazine please